Killing and captivity

When does 'radicalization' mean back to the roots?

What are the connections between the origins of an ancient faith and the behavior of its modern-day adherents? Do people commonly make those connections in reasonable and relevant ways? Does the present state of public discourse in western societies allow for open, honest, and authentic discussion of these connections?

Academic scholarship on the origins of Islam involves careful study of a range of early Muslim genres. Chief among them, of course, is the Muslim scripture, the Quran. But we can’t actually learn from the Quran about how Muslims believe it came to be. For that story we need to turn to early Muslim narratives about Muhammad and collections of sayings attributed to Muhammad called hadith.

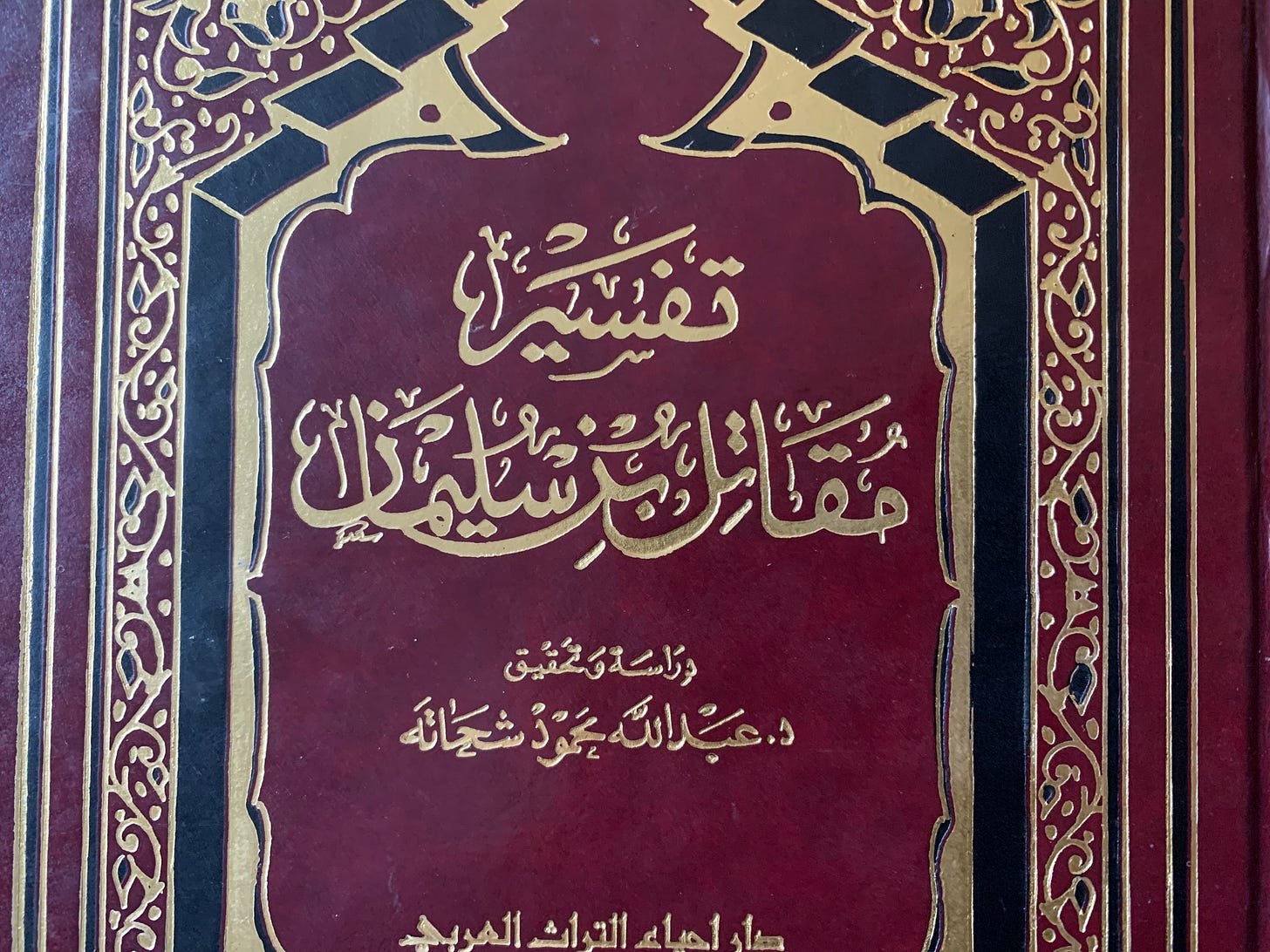

Scripture, narrative, and sayings first mingle in works of Muslim commentary on the Quran known as tafsīr. This was my own avenue into study of the origins of Islam during PhD research. My professor directed me to what he understood to be the earliest complete Muslim commentary on the Quran, a tafsīr attributed to Muqātil ibn Sulaymān, who according to Muslim tradition died in 767 A.D.

I pursued my research into this commentary during the next few years. At the time, the commentary had only recently been published in Cairo, and there were very few secondary studies on Muqātil and even fewer passages of translation out of Arabic. As I traced a particular theme in the commentary (which I will write about here Lord willing in due course), I translated a long passage from Muqātil’s interpretation of the famous Second Sūra. This was to provide general context for the particular verse interpretations I’d focused and, as it turned out, to provide a ready answer to accusations of ‘cherry picking.’

Now a couple of decades later I am finally getting around to publishing the translation with the original Arabic on the left-hand facing page and a series of helpful notes that parallel the introduction. Several publishers have shown interest. Since translating the Sūra 2 passage I had also translated a large part of Muqātil’s commentary on Sūra 3 for further writing projects, and now my American scholar friend Dr. Ayman Ibrahim has helped me prepare that translation for the book as well.

Completing and checking these translations since October 7, 2023 has caused me repeatedly to hold side by side an eighth-century Muslim worldview and reports of a twenty-first-century massacre. Feeling shaken during the following month, I wrote a substack here directly questioning Canadian celebrants of the massacre whether they were familiar with the Hamas Covenant and whether they meant to affirm its intentions. Up to that point, Hamas and its covenant had merely been a unit that I taught in university courses on ‘Islam in the modern world.’ An academic topic had suddenly sprung to life.

I pointed out in that November 2023 substack that not only was the Hamas Covenant specifically and meticulously Islamic, but that it explicitly excluded all non-Muslim approaches or contributions to the Palestinian political situation. Out of academic study of Islam and practical experience of Muslim communities in Pakistan, India, and elsewhere, the Hamas Covenant seemed to me to be expressing fundamental Muslim beliefs (‘fundamental’ is not a pejorative for most Muslims). But my substack on the Covenant drew no significant answer and — even till today — only one like!

(I freely acknowledge that this column has a very limited reach and that I have neither time nor smarts to publicize it appropriately. But even so, did low response indicate low interest in my questions? Was it a matter of not wanting to speak at the time?)

Muqātil’s interpretations of Sūras 2 and 3 are lively with narrative about the reactions of Jews and Christian to the earliest Muslim truth claims. Along with superlative claims for Islam, the ‘messenger,’ and his recitations, the commentary narrates a series of polemical attacks on Jews and Christians, their beliefs, and their behavior. These attacks are much harder on Jews than on Christians. The commentary makes clear that Muslims brought these disputes to the long-standing religious communities of the Middle East rather than the other way around.

To my mind this is quite natural and perfectly acceptable. People of different faiths will disagree, will defend their own beliefs, and will question and even declare false the beliefs of others. Muqātil in fact repeatedly called Jews and Christians unbelievers because they did not accept the claims of Islam.

When the narrative went beyond verbal apologetic and polemic, however, I noticed that Muqātil assumed physical punishment for what he understood to be unbelief (especially disbelief in Muhammad, see e.g. at Q. 2:41). Interpreting a verse that promises ‘payment’ both ‘in the present life’ and ‘on the day of resurrection’ (Q 2:85), Muqātil wrote that ‘killing and captivity’ came to a Jewish tribe in Medina called Qurayẓa, and ‘expulsion and banishment’ was the lot of a second Jewish tribe called Naḍīr. Further along in the commentary, at 2:109, Muqātil claimed that this took place at the command of Allah. and then at 2:137 that Allah himself was the actor. Yet the well-known tales of these episodes in the early Muslim narratives picture the very human Muslims of Medina carrying out these punishments. (For subscribers who do not read Arabic, the most accessible early Muslim accounts of these episodes are two English translations, both titled The Life of Muhammad, one by Ibn Isḥāq [d. 767], Oxford 1955, pp. 437-45 and 461-82; and the other by al-Wāqidī [d. 823], London 2011, pp. 177-88 and 244-61.)

Killing and captivity. Fast forward to Hamas in 2023. Is there a connection?

Current western news reports and opinion pieces about Islam often use the language of ‘radicalization’ in an apparent effort to isolate a variety of Muslim commitment that they dislike (seen very recently in Canada’s National Post). But the word ‘radical’ originated from the Latin radix, meaning ‘roots.’ In common English usage, we often use ‘radical’ to refer to roots or fundamentals. Is this the meaning we give to ‘radical’ Islam?